Categories

Immediate Kangaroo Mother Care: this may be the best ‘medicine’ in newborn care!

Over the past two decades, although there has been a significant decrease in child mortality rates, newborn mortality rates have not experienced the same decline. Unfortunately, today, approximately 1.6 million infants born prematurely or with low birth weight pass away within the first month.

Consequently, it is crucial to identify effective measures that can improve outcomes for newborns.

Ever since I first saw the incredible benefits of Kangaroo Mother Care, when assisting premature newborn triplets in 2006 being cared for under the expert guidance of the superbly experienced Professor Olugbenga Mokuolu, I have borne witness to the positive outcomes of physical proximity demonstrated in the effectiveness of the simple yet impactful kangaroo mother care (KMC).

This intervention involves placing the baby on the mother’s chest immediately after birth and then facilitating prolonged skin-to-skin contact while emphasising breastfeeding. This powerful approach has numerous benefits for both the baby and the mother; through regulating the baby’s body temperature, promoting stable heart and respiratory rates, enhances breastfeeding initiation and duration, saving numerous infants’ lives worldwide.

My Wellbeing Foundation Africa champions breastfeeding and kangaroo mother-care in partnership with Medela Cares, empowering mothers and babies to establish lactation within neonatal intensive care unit’s across Nigeria. Containing the optimal and essential nutrients, antibodies, and growth factors that support the development of #NICU babies, while also protecting them against infections and diseases, breast truly is best. Breastfeeding also promotes the bonding and emotional connection between the baby and their mother, as the close physical contact stimulates the release of oxytocin, the “love hormone,” fostering a sense of security, comfort and emotional wellbeing.

Also recently highlighted in an article by the Gates Foundation, #KMC immediately after birth could save 150,000 more lives each year globally. My Wellbeing Foundation Africa #frontline midwives, nurses and healthcare workers recognise and utilise the transformative potential of #KMC through providing continued education, training, and support in the #NICU setting, ensuring that every infant not only survives but thrives.

As our collaborative efforts advance healthcare practices but also establish sustainable change within communities, we can create a brighter future for the most vulnerable among us and ensure that every newborn receives the nurturing support they deserve.

At the Gates Foundation, Hema Magge, a senior program officer and a paediatrician/researcher, wants to see more widespread use of KMC, regardless of the pandemic. She calls KMC an “utterly human and humane intervention, but with all of the scientific data behind it. That’s what makes it so powerful.” She also understands its challenges. Here she shares her views on the subject:

One of my favourite photos is from the years I spent working with the Rwanda Ministry of Health to establish some of the country’s first rural neonatal intensive care units, or NICUs. The photo shows a midwife I knew named Claudine, along with a mother and her tiny baby laying across her chest—skin to skin, the two of them wrapped together in a blanket. The baby, born early, has a feeding tube to receive her mother’s milk despite being unable to breastfeed. The midwife embraces the mother warmly. Though the mother has just gone through a difficult birth, she gazes at the camera with a look of joy. This is what the first days of getting to know your child should feel like—full of love, support, and solidarity.

One of my favourite photos is from the years I spent working with the Rwanda Ministry of Health to establish some of the country’s first rural neonatal intensive care units, or NICUs. The photo shows a midwife I knew named Claudine, along with a mother and her tiny baby laying across her chest—skin to skin, the two of them wrapped together in a blanket. The baby, born early, has a feeding tube to receive her mother’s milk despite being unable to breastfeed. The midwife embraces the mother warmly. Though the mother has just gone through a difficult birth, she gazes at the camera with a look of joy. This is what the first days of getting to know your child should feel like—full of love, support, and solidarity.

This is a wonderful example of the power of kangaroo mother care (KMC), which supports a natural and powerful human process that provides warmth, bonding, and physiological stability. It’s adaptable and can be used alongside oxygen therapy, intravenous fluids, and even more intensive respiratory support. And it has been shown repeatedly to be extremely effective in reducing mortality in preterm and low-birth-weight babies—more effective, even, than some high-tech interventions such as incubators.

Lessons from the kangaroo mother care ward

I will confess that when I first encountered KMC more than a decade ago, I was a bit sceptical. The issue wasn’t KMC itself. I believed that keeping babies close to their mothers after birth, with skin-to-skin contact and breastfeeding, was protective on many levels. But there was a sense back then that the global development community was promoting KMC as a cheap fix in places where “modern” neonatal care wasn’t available. To me, it felt like a way to avoid confronting the injustice of under-resourced health systems in poor countries. In well-equipped hospitals, small or sick babies were whisked from their parents, supported with the latest technology, and put in incubators. At the time, I felt we should be talking more about how to ensure universal access to high-tech neonatal units like those where I trained in the United States.

I was also disheartened by what I saw in many KMC wards. Often, I’d see babies wrapped in blankets, not on a caregiver’s chest. Why weren’t the nurses putting the babies in the kangaroo position? And when mother and baby were wrapped KMC style, I sometimes got the sense that the mothers weren’t comfortable, that they felt trapped. I knew they wanted the best for their babies; so why weren’t they embracing this lifesaving practice?

I started to dig deeper, listen, and learn. I spoke with the mothers, and they taught me so much. Some felt scared to hold their tiny baby or were concerned that the baby would be cold without clothes. Others weren’t sure the baby would be safe wrapped onto them, especially if the baby was hooked up to oxygen or IV tubes. How could she provide skin-to-skin contact continuously after birth when her own body needed to recover? How could she go to the bathroom? Or prepare her own meals (since hospitals didn’t provide them)? Or get rest when hospital policies didn’t allow even her husband to visit? When I visited mothers at home after discharge, I understood how hard it must have been to stay in the hospital with a preterm infant for days or weeks when she had other children at home who needed her.

I listened to the nurses, too, and began to understand the time and energy required to care for 15 babies as the sole nurse while also addressing the mothers’ concerns, fears, and needs. I began to see how caring for a baby in an incubator—where it’s easy to monitor vital signs, change IVs, and conduct labs—could feel more straightforward in some situations. Suddenly what was billed as a “simple solution” became much more complex. For me, it was a lesson. Properly using KMC would require a culture change. Health systems would have to be redesigned to preserve the bond between mother and baby and keep them together even when the baby needs additional medical support. Infrastructure and policies would need to change. And most of all, mothers would need to be treated with dignity.

Many trials have demonstrated the clinical, nutritional, and developmental benefits of KMC, but there still has been a reluctance to use it, especially with the smallest and sickest infants.

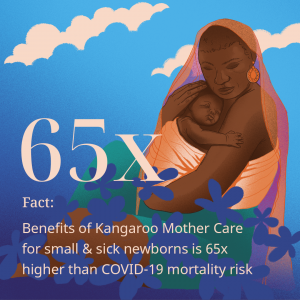

The Gates Foundation funded a trial to see if this benefit could be extended safely to infants weighing just 1 to 1.8 kilograms (around 2 to 4 pounds) who were thought to first require incubator stabilization. As it turned out, the trial had to be stopped early because immediate KMC was saving so many more lives than the standard of care.

My experience in Rwanda, coupled with the volumes of research, made me think more deeply about how health systems in wealthy countries have evolved over the years toward a model of separating small and sick infants from their mothers. In a typical NICU, there isn’t even a place for a parent to sit or lie with a baby on their chest. A mother’s life-sustaining warmth, heartbeat, and gentle breathing are replaced with machines. This is happening more frequently in poor countries, too. But it’s clear to me now that in applying this scientific lens—or what we thought was scientific—we are disrupting the natural human experience. We’re also not providing the best possible care to preterm infants. Now both rich and poor countries have the challenge of undoing this harm.

KMC and COVID-19

Certainly, COVID-19 has seriously disrupted maternal, newborn, and child health care, with both maternal mortality and stillbirths rising sharply in some settings. But this disruption has also presented opportunities, not only by exposing the fragile nature of maternal and child health—and health care systems more broadly—but by doing something to stop preventable deaths. KMC is an entry point into reimagining how to provide person-centred, comprehensive care for small and sick newborns and their mothers. The foundation is now working with WHO, UNICEF, and other global partners to support integration of KMC.

I’m optimistic that more and more doctors and nurses will recognize the transformational power of KMC. I saw it happen in Rwanda. Step by step, the hospital team started to address the issues the mothers and nurses identified. They began rethinking the physical design of neonatal units and care delivery processes and recognizing the caregivers’ expertise.

Bolstered by the power of community and shared experience, they began realising the vision of KMC. I also see it happening in some of the best-resourced medical centres, including NICUs here in Seattle that are incorporating KMC into their care of premature infants, learning from experiences in Africa, Asia, and South America.

That vision is what I see in the photo. My friend Claudine was a clinical provider, ally, and advocate for baby and mother together. The mother felt respected and had her needs prioritised while nurturing her baby’s health. When the right tools are in place, you can walk into a KMC unit and see mothers and health care workers smiling. We just have to listen to the experts—mothers and caregivers—to do it right.

Categories